NASA recently announced the discovery of a solar system with seven earth-sized rocky planets, three of which could potentially sustain life. Interesting news, but at 235 trillion miles away, no one is going there soon. In the meantime, we need to look after our only home. We must protect ourselves from climate change. Our fate turns on a race between physics and politics. The physics of climate change is off and running—we’re not sure how fast, and we don’t truly know the end point. But we do know that in the last century, dramatic increases in fossil fuel burning and changing land use began fundamentally changing the composition of the atmosphere. Warming has already raised sea levels, caused ocean acidification and coral reef bleaching. It contributes to depleted biodiversity, droughts, mass migration and extreme weather events including recently extreme high temperatures in the Arctic, heatwaves in Australia, drought in Bolivia, famine in north east Africa, flooding in the United States. As for the politics, even before Donald Trump, our response had been too slow. The most instructive single metric is the parts per million (ppm) of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which not merely continues to increase, but to accelerate. Over the last 50 years the average increase was 1.7 ppm; in the last five 2.5 ppm. We need to up our game. In 2015, it seemed possible to hope after the world came together to tackle climate change in Paris, helped by a newly positive US approach. Then last year, the prospect of a Trump presidency galvanised countries to ratify in record time. The Paris Agreement included a clear statement: in the second half of this century, all man-made emissions of greenhouse gases must be reduced to zero or be captured and stored. It falls to our generation to make this happen. The difficulty is we must do so through national politics, which find it hard to deal with threats that straddle borders and have an inbuilt time lag so that consequences only unfold in the distant future. The charge that other countries are free-riding is always a powerful excuse for inaction. And that has even more sting now that Trump has begun rolling back domestic environmental protections, and suggesting he may even withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement. But is Paris, and the multilateral spirit it embodies, really doomed? The UK’s Climate Change Act demonstrates the multilateral merit in setting a unilateral example. A recent report by the Grantham Institute lists over 800 climate change-related laws now in place in 99 countries. Most recently, Sweden published legislation setting a net zero target by 2045, citing the UK’s climate act as its model. Thankfully there are also signs that much of the rest of the world—most importantly China and India—will stick to their efforts to begin to decarbonise and the EU Commissioner during his visit to China this week emphasised the importance of continued EU-China collaboration and leadership.

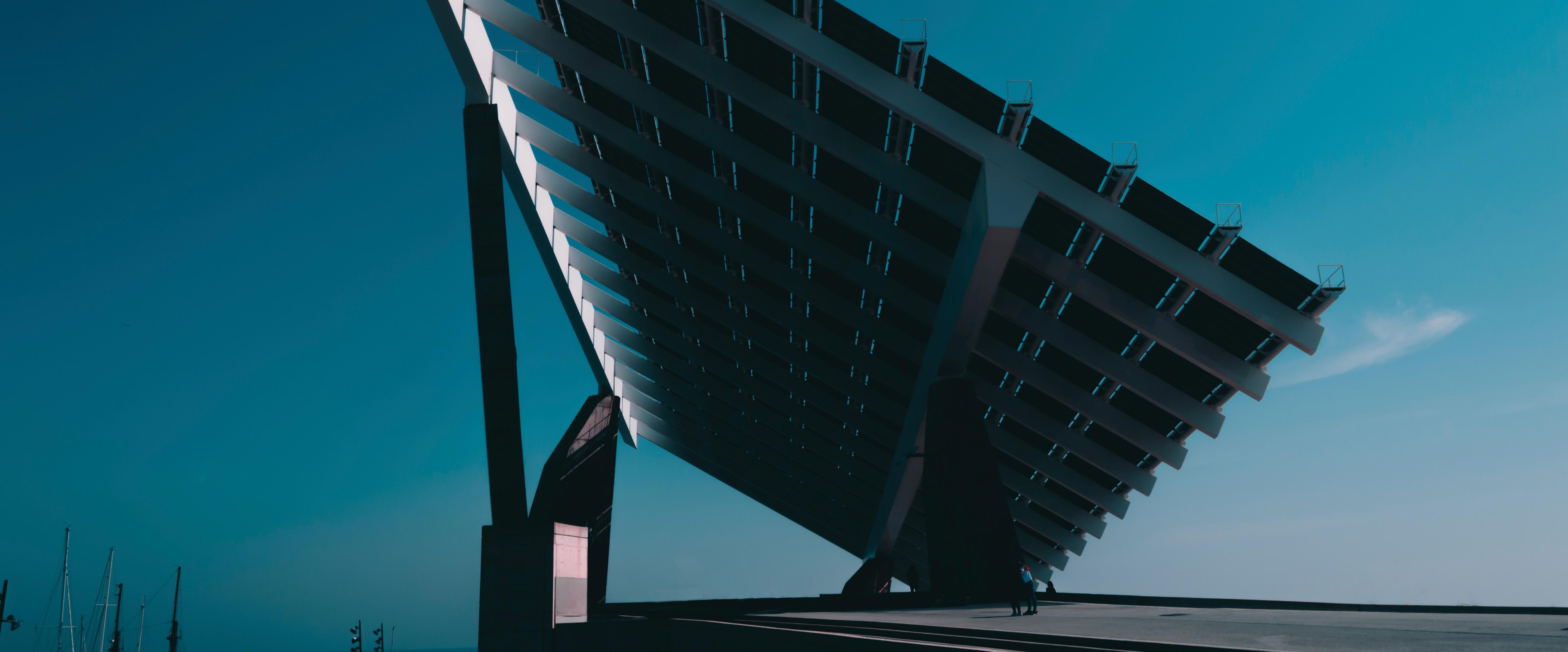

CLIMATE AND ENERGY

Climate change is a severe and increasing risk to global society but, in solving it, we will also address many other environmental problems, such as poor air quality. Our approach is to find ways of accelerating the transition to a zero net emissions economy.